What W. E. B. Du Bois Conveyed in His Captivating Infographics

Du Bois described the materials that he had selected as “an honest straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.” He added, “In a way, this marks an era in the history of the Negroes of America.” The exhibition won awards in Paris, and it then toured the United States, where Americans were beginning to regard the decades since the Civil War as a discrete epoch.

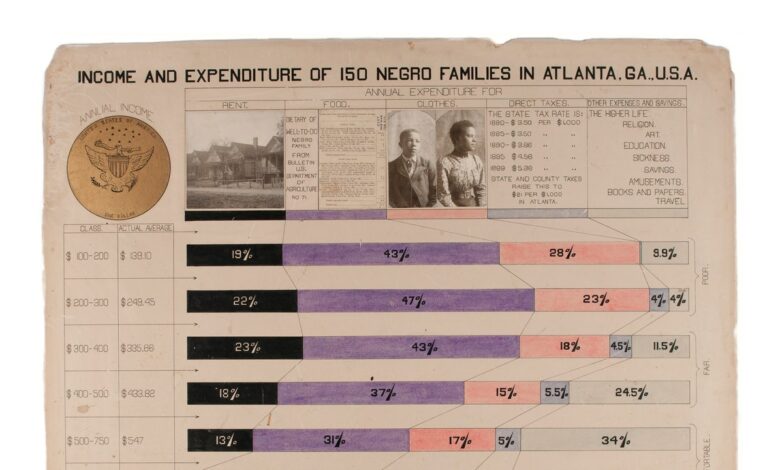

Du Bois’s charts and graphics return to the public consciousness every few years, in part because there’s something so unexpected about them. Just last year, the W. E. B. Du Bois Center at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and Princeton Architectural Press published “W.E.B. Du Bois’ Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America.” As the design scholar Jason Forrest has argued, in a series of essays on the data visualizations’ craft and design, one of the reasons for their enduring appeal is the contemporary viewer’s surprise that they look so modern. It’s easy to assume that Du Bois and his team aspired to make art; the graphics suggest the front page of USA Today, if it were reimagined by the Suprematist painter Kazimir Malevich. But the informational graphics that Du Bois and his team crafted followed early-twentieth-century approaches to visualizing data. The results display resourcefulness, creativity, and a commitment to communicating their truths clearly and directly.

In “Black Lives 1900,” Rothenstein seeks to emphasize the relevance of Du Bois’s work through juxtaposition: materials from the original exhibition are interspersed with excerpts from Du Bois’s own writings and more recent remarks from writers including Maya Angelou and Ta-Nehisi Coates. These interstitial selections seem intended to conjure a continuum of black voices, or perhaps to argue that the insurmountable prejudices of Du Bois’s day linger in the present. The connections can feel heavy-handed; the book is best when it leaves room for the reader to reflect on what Du Bois and his spectators might have seen or thought in their own time.

Thirty-five years after the Paris Exposition, Du Bois published “Black Reconstruction in America.” In it, he imagines what might have been had the ruling class not exploited the racial divisions between poor whites and former slaves after the Civil War. Sifting through the Paris materials, one can find the seeds for this later project. The missed opportunity of Reconstruction, Du Bois argues, was that these two dispossessed groups had failed to recognize their common plight. Something else was possible. For a spell, black life had flourished, and he had the evidence: a portrait of a young woman grinning to herself, and radiant charts that indicated a growing slice of the pie.