Unlikely allies in the Atlanta nonprofit World

Some might wonder what would an arts organization and an organization working for criminal legal reform have in common. Ariel Fristoe, founder and Artistic Director of Out of Hand Theater, and Doug Ammar, Executive Director of Georgia Justice Project (GJP), discuss the unique collaboration between the Atlanta-based nonprofits they represent.

Can you introduce yourselves?

AF: I’m Ariel Fristoe, founder and Artistic Director of Out of Hand. Our mission is to use the tools of theater to help create a more just world. We do that by combining short plays and films with information and conversation. All our programs include art to open hearts, information to open minds, and conversation to inspire action. We make programs for community partners and bring them to people’s homes, businesses, schools and houses of worship.

DA: I’m Doug Ammar, Executive Director of GJP. Our mission is to reduce the number of folks under correctional control in Georgia and to reduce barriers to reentry. We’ve worked towards that mission by doing three things. First and foremost is direct service, which means representing people as lawyers, following our clients long-term, and offering social service support. Second is policy change. We take lessons we learn from representing our clients and find solutions to implement at a higher level. Third is community engagement, which means ensuring that folks know about new laws and their rights relating to issues such as voting and probation.

GJP has always been innovative in identifying ways to increase positive outcomes for those affected by the system. We also collaborate with system actors not just to implement processes we’ve helped devise but to create mechanisms that allow more justice-involved people to access relief. We’re a small organization, and 4.5 million Georgians have been arrested or convicted. So, it’s incumbent on us to take our independent status and create more innovative opportunities for justice-involved folks to rejoin society, even if we don’t serve them as clients.

How did this collaboration begin?

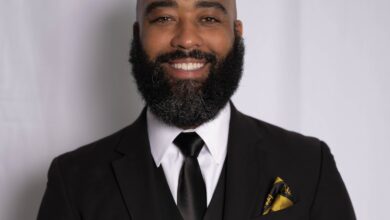

AF: Every spring, we produce Shows in Homes, which feature one actor in an hour-long show in 30 to 50 living rooms. There’s an hour of theater relating to a social justice topic, a cocktail party, and a conversation with a community partner about issues represented in the play. Before working with GJP, we’d wanted to talk about mass incarceration, but weren’t thinking about reentry. The depth of knowledge you brought to the collaboration helped us clarify the message. The play we commissioned is “Calf”, written by Leviticus Jelks, starring Marlon Burnley and directed by Nikki Young.

DA: When you reached out, we saw a chance to reach a different audience and talk to people about our work and the deeper issues underlying our work. It seemed unusual to talk to people after a play we might not know much about, but you all were flexible and willing to let us show up how we wanted to show up. That gave us a chance to clarify our messaging, determine the most important information to share, and reach new audiences in a new way.

AF: There are many critical issues that we want people to know, care, and do more about. Folks running for office often organize small, intimate fundraisers, and talk to people one-on-one. Similarly, if we want thousands of people to know more about GJP’s work, we might have to attack that in small pieces by approaching 30 people at a time in someone’s living room and giving them an intimate way to engage with the issues.

DA: Also, within our collaboration, GJP and the criminal legal issues we address felt less like an object and more like a subject. It would be easy to commission a play and invite a group for some color commentary. But our collaboration did not feel this way, because you were trying to make people aware of the issues, and you have invested your skills into one part of that equation but are inviting others to flesh out the full equation. Therefore, your partners are not objects, but subjects of the same enterprise.

AF: That’s exactly what we’re going for. Arts and entertainment are the tools that we use to lift up and serve our partner organizations.

What is the impact of this collaboration?

DA: There’s often jadedness within nonprofits when it comes to working with other nonprofits. This collaboration reconfirmed our confidence in the nonprofit sector and the utility of partnering with other nonprofits to create social change. You reminded us that there are many people in the nonprofit world willing to understand their lane of work and expertise, and to bring other organizations together to work towards a common goal. That’s why I love that, embedded in your DNA, is an understanding of your expertise and a commitment to inviting the expertise and goals of others.

AF: Our vision is to increase understanding, empathy, and action around social justice. We’re a nonprofit, so it’s important that we do good work for our community with funds entrusted to us while also demonstrating the value of the arts. We brought this program to over 1000 people, and over 90 percent of attendees reported that they had learned something new about incarceration and reentry and were moved and inspired to act on the issues discussed.

DA: For me, one benefit from this collaboration was reaching a new audience. Additionally, I don’t think of criminal legal issues as being very complex, but there are many moving parts that we work on. This was a chance to refine the narrative of our work and the issues we address within that landscape. Lastly, this collaboration opened up possibilities for future partnerships and inspired us to consider what we could do to move the needle in partnership with other arts groups.

You’ve mentioned before that many arts and criminal justice organizations are in crisis. How have you worked together to create change in this atmosphere?

AF: Theater has been in a slow-burn crisis for years, but it came to a head last summer with national headlines that said things like “theater is in freefall.” Many companies are closing, shutting down programs, or laying off staff — it’s a hard time to run a theater company. I feel lucky that I’ve found a business model where my company is thriving and growing in the midst of this crisis through collaborations like this.

DA: Criminal justice at large has been in crisis due to the war on crime and mass incarceration over the last several decades. In response to that, folks have taken a number of approaches that haven’t always been fruitful. At GJP we are focused on fighting for something, whereas others have focused on fighting against something. We also don’t only focus on the beginning of an arrest, reentry, probation, or employment — we approach it all together. We approach the long-term arch of the criminal legal system and our clients’ involvement with it on a broad scale. If we think creatively and holistically to bring hope and possibility into a difficult system, be it arts or the criminal legal system, we can make a difference and thrive.