The Green Book listed places Black travelers could visit safely during Jim Crow. Two such Danville sites will be commemorated.

During the Jim Crow era, an annual guide called “The Negro Motorist Green Book” listed businesses and amenities where Black travelers would be welcomed and safe. Today, more than half of the sites listed in the Green Book have been demolished.

Two still stand in Danville, and they will be recognized Tuesday with plaques from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources highlighting their histories.

Earlier this year, the General Assembly passed legislation calling for plaques that identify Green Book sites to be affixed to existing state historical markers. The first plaque was unveiled in Hampton in October.

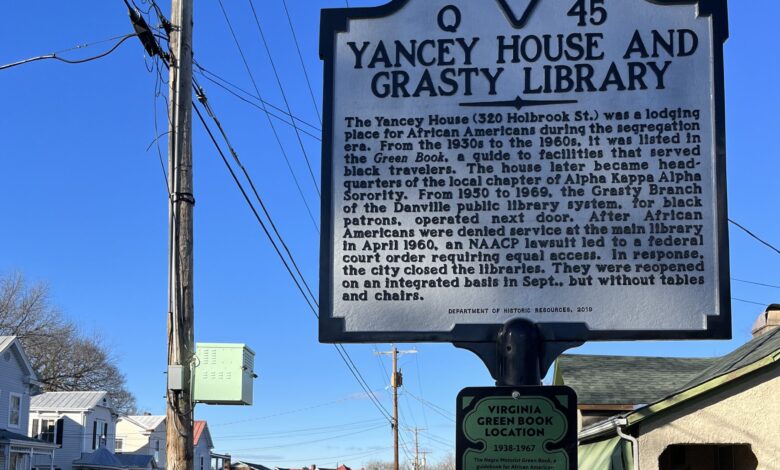

The two plaques in Danville, one for the Holbrook-Ross Historic District and one for the Yancey House and Grasty Library, are among the first five installed in the state.

“By installing supplementary plaques to historical markers at Virginia Green Book locations, the marker program will tell a more complete and inclusive history of our Commonwealth,” Julie Langan, director of DHR, said in an email.

Danville’s Holbrook-Ross Historic District, named for the two major streets that run through it, was the first neighborhood in the city for Black professionals. Black lawyers, ministers, dentists, physicians and business owners called it home in the late 19th century, according to a DHR news release.

The neighborhood grew rapidly during the 1880s, the release said, after the construction of a public school for Black students.

“By the turn of the 20th century, Holbrook Street had become the city’s leading Black residential address,” said the release. “Several businesses in the neighborhood were listed in the Green Book.”

Today, the Holbrook-Ross district is mostly made up of houses and historic churches, like Calvary Baptist Church.

Recognized together on one historic marker, the Yancey House and Grasty Library will also receive a Green Book plaque.

The Yancey House was listed in the Green Book from the 1930s to the 1960s, according to DHR. It was a lodging place for Black travelers during segregation and later became the headquarters of the Danville Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha, a historically Black sorority.

Next door, the Grasty Library was a branch of the Danville public library system for Black patrons from 1950 to 1969.

The main library branch denied services to Black residents in April 1960, which resulted in an NAACP lawsuit and a federal court order requiring equal access. In response, the city closed the library entirely.

“Danville reopened its libraries on an integrated basis in September 1960, but without tables and chairs,” the release said.

A ceremony will be held at 2 p.m. at the Alpha Kappa Alpha House on Green Street to recognize these two sites with Green Book markers.

DHR is working to designate all state markers that pertain to a Green Book location with a plaque, Jennifer Loux, the department’s historical highway marker program manager, said in an email.

There are currently seven such markers, Loux said, and three more are scheduled to be installed at locations in Richmond.

Martinsville also received a Green Book plaque recently for a marker at Fayette Street, which marks a “gateway to the business, social and cultural lives of African Americans” in the city.

Another three markers have been approved by DHR, Loux said — one each in Richmond, Lexington and Chesterfield County — but have not yet been manufactured.

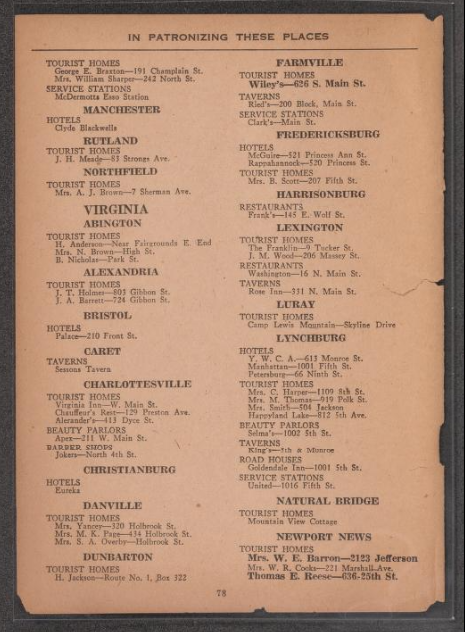

In a 1946 edition of the Green Book, two homes, a restaurant and a tavern are listed in Lexington as safe places for Black travelers. The marker will be titled “Lexington and the Green Book,” according to Loux.

Anyone who wants a particular site to be marked with a Green Book plaque in the future will first need to apply for a state highway marker through the regular application process, Loux said.

If the Virginia Board of Historic Resources approves the application, then the marker will come with a Green Book plaque when it is installed, she said. More information about the application process and the application itself can be found on the department’s website.

“Over time, as these signs are placed throughout the state, a network will take shape that will educate the public and share with them this important chapter from Virginia’s past,” Langan said.